It’s 1939 and London is preparing itself for an inevitable attack from the continent. Hetty Cartwright, once relegated to an assistant at a natural history museum, is tasked with overseeing the evacuation of countless specimens to a safe haven in the countryside. This is her chance to prove herself as a worker and as an expert—and Hetty is prepared to guard these taxidermied animals with her life. Their new home at Lockwood Manor, though, might not be so safe after all. Major Lockwood stalks through his home like a tyrant and a bully. His daughter Lucy, eerie and ethereal, walks the halls in search of ghosts and disappearing rooms. As animals begin to move and disappear in the night, and the air is cleaved apart by sirens and planes, Hetty becomes convinced of the manor’s danger. No amount of scientific reasoning can assuage her dread—or save Lucy from the very place she calls home.

Jane Healey’s debut novel, The Animals at Lockwood Manor, is a gothic queer love story with the backdrop of the Blitz rather than the moors and manners of the 18th or 19th century. But where your classic gothics more often than not portray the creeping horror and decay of the aristocracy, Lockwood Manor reveals the trauma still reverberating in its wake.

A queer gothic love story, you say? I wasn’t sure, when I picked up Lockwood Manor, if it would be textually queer or if it would just be queer in the way that the entire gothic genre is inherently queer. From the censored but still smoldering Carmilla and Picture of Dorian Gray, to the subtext of Dracula, to the more general queer themes like repression, “monstrous” desire, and social transgression of Frankenstein and all the rest—the genre is infinitely mineable as a history of queer desire and heteronormative anxiety.

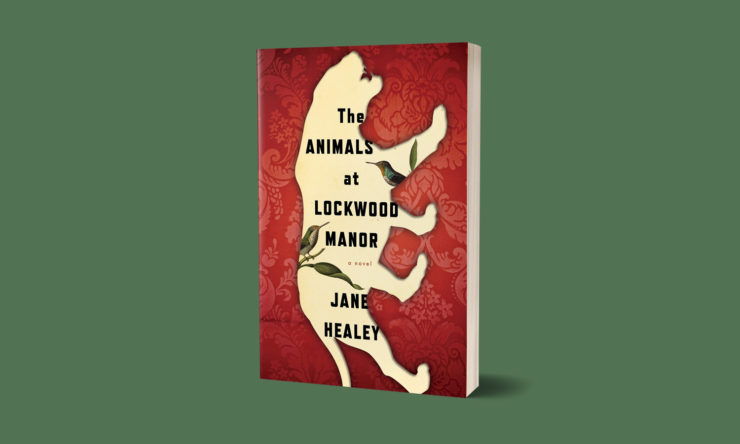

Buy the Book

The Animals at Lockwood Manor

So Healey isn’t doing anything too surprising here, by tying Hetty and Lucy’s affinities to the larger project of outsiderdom and fear—instead, she is making what was historically relegated to subtext into text. I can’t begin to tell you how satisfying that is. It felt validating, to see the growing bond between the women come to fruition, and for that bond to be treated as something precious in an otherwise terrifying and hostile setting. Besides that, the love story itself is tender and lovely, and it does its job of hurting you without pulling the rug out from under you. I don’t mind spoiling that this book doesn’t kill off its gays—let that be its own ringing endorsement.

Second to its queerness, of course, the most vital thing about a queer gothic is going to be its spookiness. Lockwood Manor is more moody and atmospheric than outright scary—despite haunting specters like the woman in white and the general creepiness of taxidermied animals, I never once felt genuinely worried for the characters’ safety. This is not a complaint, however, considering the tone and imagery go such a long way. If you’ve ever been freaked out by the uncanniness, the strangeness of nature trapped in stasis, of taxidermy—this book just leans right into it. It also does a great job of tying the creepiness of those mounted animals to its real origin—not just the animals’ cold dead eyes, but the conquering and destruction of life itself, in the name of science and colonization alike.

Lockwood Manor isn’t subtle in its critique of colonization or misogyny (which are inherently linked—in this novel as in life), though it is sometimes oblique. For instance Lucy’s mother is very much a Bertha Mason stand-in, the mad woman stolen from her home in the West Indies. Despite this, the novel does not broach a direct criticism of the racism inherent to the colonial project, even as it recognizes its overall violence and cruelty. I found myself drawn in by the ways that Healey gradually unravels the relationships between sexual violence and class and empire, and I do admire the novel’s themes overall. I don’t know that it’s saying anything that other novels dealing with these themes—of earlier eras or our own—have not already said, so part of me does wish she’d pushed it further, particularly in matters of race. Not every project can do everything, but it felt like an omission.

The Animals at Lockwood Manor reads in some ways as a pastiche of the gothic, but that’s not necessarily a critique. Like I said regarding its queerness, the book is satisfying, seeming to almost resolve the genre’s tropes rather than subverting them. Healey represents the genre well. Lockwood Manor is, above all else, engrossing and readable, luxurious in its descriptions without falling into parody. I recommend it to fans of the genre and to anyone looking for a dark read on a cold day.

The Animals at Lockwood Manor is available from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Em Nordling reads, writes, and manages research in Louisville, KY.